Expository text can be challenging to young readers because of the unfamiliar concepts and vocabulary it presents. Discover ways to help your students analyze expository text structures and pull apart the text to uncover the main idea and supporting details.

Over the past 60 years, reading comprehension has changed its emphasis from the mastery of skills and subskills that are learned by rote and automatized to a focus on learning strategies, which are adaptable, flexible, and, most important, in the control of the reader (Dole, Duffy, Roehler, & Pearson, 1991). One of the most efficient strategies for which there is an influx of research and practice is training students on text structure knowledge to facilitate their comprehension of the expository texts.

Readers of all ages must be aware of text structures if they are to be most successful (Meyer, 2003). The structure or organization of the text is the arrangement of ideas and the relationships among the ideas (Armbruster, 2004). Readers who are unaware of the text structures are at a disadvantage because they do not approach reading with any type of reading plan (Meyer, Brandt, & Bluth, 1980). However, readers who are familiar with text structures expect the information to unfold in certain ways (RAND Reading Study Group, 2002).

Students first learn to read narrative text structures, which are story-like structures that facilitate their learning to read. Consequently, students enter school having a sense of narrative structures as they appear in texts. Across the years of school, their awareness of text structures must increase as they progressively shift from reading a story line or casual text to reading for information (Lorch & Lorch, 1996). By the third grade, and obviously by the fourth, there is a noticeable shift to reading texts for information, information that is often dense and written in long passages (Gillet, Temple, & Crawford, 2004; RAND Reading Study Group, 2002).

According to The Nation’s Report Card (National Center for Education Statistics, 2009), no significant differences in achievement of fourth graders were observed across groups. A part of this could be due to the ineffectiveness of current teaching techniques applied in reading classes. Reading teachers may find teaching text structure for expository texts an effective technique to improve reading achievement averages.

Most expository texts are structured to facilitate the study process for prospective readers. These texts contain structural elements that help guide students through their reading. Authors of expository texts use these structures to arrange and connect ideas. Students who understand the idea of text structure and how to analyze it are likely to learn more than students who lack this understanding (RAND Reading Study Group, 2002). The research literature in this field reveals that students’ reading comprehension skills improve when they acquire knowledge of texts’ structural development and use them properly.

Carrell (1985) argued that instruction on text structure indeed has a positive effect on the students’ recall protocols. Meyer (1985) stated that knowledge of the rhetorical relationship of the ideas- main idea , major ideas, and supporting details-helps readers with their comprehension of the expository texts. Reading researchers have argued that knowledge of text organization or structure is an important factor for text comprehension (see Aebersold & Field, 1997; Fletcher, 2006; Grabe, 1991, 2004, 2008; Hall, Sabey, & McClellan, 2005; Horiba, 2000; Kendeou & van den Broek, 2007; Meyer, 2003; Meyer & Poon, 2001; Snyder, 2010).

Text features can help readers locate and organize information in the text. For example, headings help introduce students to specific bits of information. Presenting information in this manner helps students hold each bit of information in their short-term memory. Students then can process it or connect it to background knowledge and store it in their longterm memory. Without headings, information would be overwhelming, making it difficult to be processed effectively.

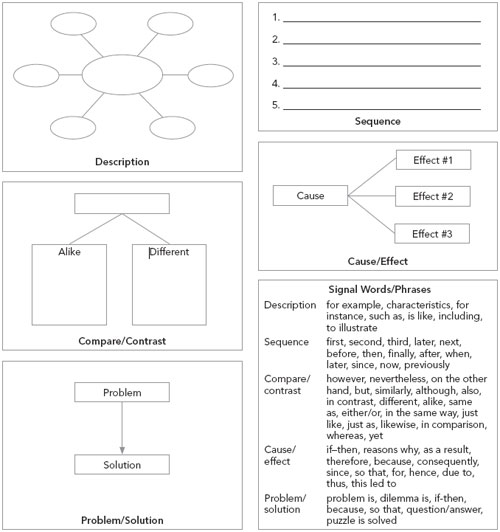

Structural elements in expository texts vary; therefore, it is important to introduce students to the components of various texts throughout the school year. It is also important to teach and model the use of these components properly at the beginning of the school year. The recognition and use of text organization are essential processes underlying comprehension and retention. As early as the third grade, students are expected to recognize expository text structures. Meyer (1985) classified these text structures as follows:

The ability to identify and analyze these text structures in expository texts helps readers to comprehend the text more easily and retain it longer. To achieve better results, it is highly recommended to introduce and work on text structures in the order prescribed in what follows.

Another powerful and effective method is to begin with the comparison text structure, followed by cause and effect and problem and solution. Sequence and description are left to the end because children are quite familiar with them and don’t appear to need additional help with those. See this article, Implementing the Text Structure Strategy in Your Classroom, for a detailed description.

Tompkins (1998) suggested the following three steps to teach expository text structures:

Having applied the procedure recommended by Tompkins (1998), we would like to share our own experience in teaching expository text structure and shed more light on the practical aspects of teaching text structure in reading classes. The first and most important thing for you as a teacher is to be well informed about different text structures for expository texts, the signal words and phrases for each text structure, and the appropriate graphic organizer specific to each text structure.

Before you prepare any instructional plan to start training students and embark on reading activities, you must model all the procedures. Meanwhile, the students watch you focusing on the steps you have mentioned, from recognizing the signal words and phrases to applying the graphic organizers to each text. After you have practiced for the first few sessions and students have collected enough background on what they are going to do, it is time to use the following recommended procedure:

Find downloadable templates here: Teaching Text Structure

As the students progress to the final stage, they are able to use the signal words and phrases as a clue to recognize the rhetorical structure of the text and create the appropriate graphic organizer for each text structure. They are capable of identifying the main idea, other major ideas, and supporting details of the text and put them in the graphic organizer to illustrate the subordination of the details to the main and major ideas.

As students progress through school, they face having to read challenging texts, texts that require them to read for information instead of simply reading for the text. Ask them to recognize the rhetorical fun. As students learn to read, they should learn to recognize different text structures so they can predict what type of information is included. Consequently, the basic need is for teachers to teach students to identify text structures and decide what information is most important in their readings.

Reading expository texts is critical for growth in reading ability and most urgent to rank normal achievers; the ability to read, comprehend, and analyze expository texts (i.e., identifying main idea , major ideas, and supporting details) could be good criteria to rank students’ academic reading achievement. One way to measure and rank students’ reading achievement of the expository texts is to teach reading through text structures. This will raise text structure awareness and is assumed to lead to a permanent improvement in reading skill.

Aebersold, J.A., & Field, M.L. (1997). From reader to reading teacher: Issues and strategies for second language classrooms. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Armbruster, B.B. (2004). Considerate texts. In D. Lapp, J. Flood, & N. Farnan (Eds.), Content area reading and learning: Instructional strategies (2nd ed., pp. 47-58). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Carrell, P.L. (1985). Facilitating ESL reading by teaching text structure. TESOL Quarterly, 19(4), 727-752. doi:10.2307/3586673

Dole, J.A., Duffy, G.G., Roehler, L.R., & Pearson, P.D. (1991). Moving from the old to the new: Research on reading comprehension instruction. Review of Educational Research, 61(2), 239-264.

Fletcher, J.M. (2006). Measuring reading comprehension. Scientific Studies of Reading, 10(3), 323-330. doi:10.1207/ s1532799xssr1003_7

Gillet, J.W., Temple, C., & Crawford, A.N. (2004). Understanding reading problems: Assessment and instruction (6th ed.). Boston: Pearson.

Grabe, W. (1991). Current developments in second language reading research. TESOL Quar terly, 25(3), 375 - 406. doi:10.2307/3586977

Grabe, W. (2004). Research on teaching reading. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 24, 44-69. doi:10.1017/S0267190504000030

Grabe, W. (2008, May, 29-31). Using graphic organizers to help develop reading and writing skills. Paper presented at the TESOL conference, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Hall, K.M., Sabey, B.L., & McClellan, M. (2005). Expository text comprehension: Helping primary-grade teachers use expository texts to full advantage. Reading Psychology, 26(3), 211- 234. doi:10.1080/02702710590962550

Horiba, Y. (2000). Reader control in reading: Effects of language competence, text type and task. Discourse Processes, 29(3), 223-267. doi:10.1207/S15326950dp2903_3

Kendeou, P., & van den Broek, P. (2007). The effects of prior knowledge and text structure on comprehension processes during reading of scientific texts. Memory & Cognition, 35(7), 1567-1577.

Lorch, R.F., & Lorch, E.P. (1996). Effects of organizational signals on free recall of expository text. Journal of Educational Psychology, 88(1), 38-48. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.88.1.38

Meyer, J.B.F. (1985). Prose analysis: Purposes, procedures, and problems. In B.K. Britten & J.B. Black (Eds.), Understanding expository text: A theoretical and practical handbook for analyzing explanatory text (pp. 11-64). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Meyer, J.B.F. (2003). Text coherence and readability. Topics in Language Disorders, 23(3), 204-224. doi:10.1097 /00011363 -200307000 -00007

Meyer, J.B.F., Brandt, D.M., & Bluth, G.J. (1980). Use of top-level structure in text: Key for reading comprehension of ninthgrade students. Reading Research Quarterly, 16(1), 72-103. doi: 10 .2307/747349

Meyer, J.B.F., & Poon, L.W. (2001). Effects of structure strategy training and signaling on recall of text. Journal of Educational Psychology, 93(1), 141-159. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.93.1.141

National Center for Education Statistics. (2009). The nation’s report card. Reading 2009: National Assessment of Educational Progress at grades 4 and 8 (NCES 2010-458). Washington, DC: Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education. Retrieved November 2, 2010, from nces .ed .gov / nationsreportcard/reading

RAND Reading Study Group. (2002). Reading for understanding: Toward an R&D program in reading comprehension. Santa Monica, CA: RAND.

Snyder, L. (2010). Reading expository material: Are we asking the right questions? Topics in Language Disorders, 30(1), 39-47. doi: 10.1097/TLD.0b013e3181d098b3

Tompkins, G.E. (1998). Language arts: Content and teaching strategies. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill

Structure to Facilitate Reading Comprehension. The Reading Teacher, 64: 368-372. doi: 10.1598/RT.64.5.9Akhondi, M., Malayeri, F. A. and Samad, A. A. (2011), How to Teach Expository Text